Knowledge

Pointers from Seychelles

From humble beginnings to a Best Practice Hub

March 26, 2018

Did you know that Seychelles, an archipelago of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean, is among the world leaders in early childhood and care education (ECCE)? Formally recognized by the IBE as a Best Practice Hub, Seychelles is committed to ensuring holistic development of children, starting even before they are born. How and why has Seychelles made ECCE a priority?

Photograph: Alamy

Without quality ECCE services, people have lower chances of employment, lower productivity, and lower earnings. And the country has lower rates of economic growth, more intergenerational poverty, and more social maladjustment, including high incarceration rates. And the list goes on.

By Macsuzy Mondon & Shirley Choppy

26/03/ 2018

·

- Share

Researchers have produced compelling evidence about the multiple benefits of quality Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE). ECCE offers many comprehensive services, including health and nutrition, education, and social, emotional, and legal protection for children from infancy to 8 years of age, along with parenting education for future and current parents (Marope and Kaga, 2015). Research evidence shows that when countries do not provide quality ECCE services to children in that age range, the children, and the country itself, face multiple risks. These risks include poor health into adulthood, learning difficulties, high rates of repetition and school dropout—and a lifetime without the skills one needs to become employed and to live life well. Without quality ECCE services, people have lower chances of employment, lower productivity, and lower earnings. And the country has lower rates of economic growth, more intergenerational poverty, and more social maladjustment, including high incarceration rates. And the list goes on. For all these reasons, equitable provision of quality and holistic ECCE services has remained a high priority in all key global policies and action frameworks. Examples include the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), the Millennium Development Goals (2000), the Education for All Agenda (1990, 2000), the Moscow Framework for Cooperation and Action (2010), the World Education Forum (2015), and the Sustainable Development Goals (2015). ECCE is also mentioned or at least implied in many national policy statements, including those made when the countries sign UN declarations, constitutions, and sector policies and programs. However, most countries still find it a daunting challenge to ensure universal access to quality ECCE services, especially for disadvantaged communities. In these communities, people face limited access to core ECCE services such as pre- and post-natal care, nutrition, health and sanitation, crèches, and pre-primary education. And other troubling conditions exist: neglect, poor parenting, and lack of political support.

Humble Beginnings

When countries were being challenged to deliver quality ECCE services to all children, Seychelles was no exception. But the country did have some strengths on which it could build a holistic, effective, and equitable ECCE system. It had implemented universal access to primary schooling, and quite a high percentage of children were participating in pre-primary education. Healthcare was free for all. Other key programs were fairly institutionalized. These included maternal and child health in the health sector, partial education provision for preschoolers in the education sector, broad child protection services in the social sector, and periodic community programs for school children.

However, the country still faced critical impediments as it worked to develop a progressive ECCE system. The primary challenges were real, and complex, though sometimes subtle. Overall, ECCE provision had been neglected, more by omission than on purpose. One clearly omitted, but crucial, element was a common view or concept of ECCE that could unite all providers around a common purpose and agenda. Moreover, the resources allocated for ECCE were neither adequate nor equitable. Most staffers were unqualified, so the learning programs were weak and irrelevant. Although healthcare had been available, the quality of services was varied, inconsistent, and not thoroughly supervised. Only limited interventions were available for children with developmental delays. Parenting programs were very restricted in coverage, and the school nutrition program faced serious difficulties in implementation. Planning for the child protection system was poor and no programs were targeted to children in the early years. No priority was placed on providing day care facilities across communities; this negatively impacted access and effective participation. Collectively, the prevailing challenges could be grouped into three categories.

Salience

As more and more scientific and economic evidence demonstrates the developmental power of ECCE, the challenge in Seychelles was to reduce the knowledge gap and raise the level of awareness of ECCE among practitioners, professionals, politicians, community members, and the general public. It was crucial to draw attention to ECCE, to advocate for it, and to create a political and academic environment, including greater public knowledge, that would emphasize the importance of holistic early childhood development that encompasses the aspects of health, nutrition, stimulation, and protection.

Integration

Given the multi-dimensional nature of ECCE, various sectors had tended to offer ECCE services in isolation. Further, some aspects of ECCE services remained hidden among the policies and programs in various sectors; this made it difficult for ECCE to stand out as a holistic service in its own right. Aspects of ECCE services were fragmented at best; at worst, they could actually undermine each other, albeit unintentionally. The country desperately needed an approach that operated better both within and between sectors to pull together the contributions of different sectors and improve the overall impact of holistic early development for Seychellois children. Locating an ECCE center in any ministry, including those of education and health, was controversial and not likely to lead the different sectors to contribute in a balanced and effective way. It was simply a national imperative to harmonize and coordinate efforts, programs, and services across sectors.

Monitoring

To sustain and continuously improve ECCE provisions requires constant monitoring and periodic evaluation. The lack of such functions made it very difficult to deliver services and implement programs. On the whole, data were not being used adequately to set a baseline for assessing the impact of projects, in order to communicate progress. The country needed monitoring research to develop tools for measuring development outcomes and to improve indicators of quality; it also needed a robust monitoring mechanism at all levels of the system to provide feedback on performance and achievements, and to assess service conditions. Monitoring was also vital to ensure that standards would be adhered to and regulations followed. This was a prerequisite for supervisory work and accountability reporting, and it needed the support of a strong statistical and data management system.

The turning point

The state of ECCE in the country had always been a source of discomfort among the few experts in the field. They clearly saw the need for a reform process that would address the concerns, constraints, and inconsistencies— and the need to unify the different agencies and move the country’s ECCE agenda forward. But the real turning point occurred in Moscow in 2010, when our then Right Honorable Vice President, Danny Faure, took a leadership role in the first UNESCO-led World Congress on Early Childhood Care and Education (WCECCE). As one of the core political leaders of the WCECCE, Rt. Hon. Danny Faure had the last word on the WCECCE. In his closing speech, he implored all the 130+ participating countries to go forth and make the conference document, the Moscow Framework for Action and Cooperation: Harnessing the Wealth of Nations, a reality for all the world’s children. Most importantly, he promised to go back home and lead by example. Indeed he did!

Toward a Best Practice Hub

Under Rt. Hon. Danny Faure’s inspiring leadership, several key factors were—and still are—pivotal in turning ECCE around in Seychelles: political leadership, policy direction, institutional structures, national action planning, collaborative partnerships, and policy research.

Political leadership

To chart the course and set Seychelles on a successful path towards using best practices, political leadership was the most important factor. It was crucial to have political commitment and confidence in a leader who champions ECCE. Rt. Hon. Danny Faure honored the country’s pledge by setting up a multi-sectorial National Steering Committee for ECCE, almost immediately upon his return from Moscow. This committee was instrumental in defining the policy direction for ECCE in Seychelles through the development of the Seychelles Framework for Early Childhood Care and Education.

Policy direction

The framework is an overarching policy document that involves not only ECCE sectors but also “all other stakeholders in ECCE”. It sets out and articulates a united vision: “a winning start in life for all children in Seychelles: a shared commitment”. It outlines 8 guiding principles: child-centeredness, parental engagement, collaborative work, long-term sustainability, active learning, training and professional development, accountability, and cultural appropriateness. It identifies thematic priorities, including policy realignment, community provisions, child protection, and quality standards. It proposes a renewed governance structure with a high-level ECCE policy committee and sectorial teams working toward technical implementation. It emphasizes that monitoring and data management are necessary for successful implementation and effective reporting.

Institutional structure

The implementation demands of the framework greatly altered institutional arrangements for ECCE, and led to the establishment of the Institute of Early Childhood Development (IECD) in 2013. The IECD is an empowered semi-autonomous body that provides strategic direction and leadership for ECCE. It has the legal mandate to promote, advocate for, regulate, and coordinate ECCE activities. This innovation drove the ECCE agenda nationally, attracted international interest, and began to shape the attitudes of professionals, parents, and the general public. IECD has become the focal point for multi-sectorial coordination and exchange. It is an academic institution where research is acknowledged. It is an entity for professional development activities. It runs advocacy campaigns for children and promotes and propagates children’s work. IECD’s ECCE forums have become a successful vehicle for disseminating information and encouraging professional dialogue and public interaction. The biennial ECCE conference, the IECD’s flagship, has become a national event for sharing progress and achievement, highlighting challenges, and promoting accountability.

National action planning

To speed the implementation of the policy framework, the IECD started, and led, a national action planning process. The National Action Plan became a binding document for the four main ECCE sectors. It covers many sectors, and encourages wide participation and outreach. The plan has also become a document for learning about ECCE. It allows actors in all sectors to clarify their plans and projects, share ideas, and cooperate within and across sectors. Within the plan, people have tried out a multi-level approach to respond to the complex challenges of integrating ECCE across institutional divides. Thus, sector-level projects or programs in ECCE are incorporated into the plans of the relevant ministries and departments. The plan provides strategic directions for selected key priority areas in the framework. For example, it places a sharp focus on a much-neglected area in ECCE: provisions for children aged 0 to 3. These responsive projects provide a rich field of experience that shapes the responsibilities of participating sectors and expands their roles. Projects such as suitability checks for child minders are extending the child protection role of the social sector. Another project draws on the facilities of community centers to provide a stimulating early learning environment for children in childminding establishments; it is both expanding the role of community workers and extending childminding provisions.

The plan has become a reference document for sectorial interchange and interaction. The Seychelles ECCE Terminology Directory is one example of collaborative work and cooperation. One critical impact of the plan is the collaboration that has been extended nationally and internationally.

Collaborative partnerships

Collaboration is the key factor in the process of transforming ECCE in Seychelles. It demands professional and dynamic interactions with individuals, sectors, organizations, and international agencies, particularly IBE-UNESCO and the World Bank. The IECD has been very successful in nurturing this process. One interactive task the IECD had to undertake was establishing a positive working relationship with ECCE sectors. In evaluating the National Action Plan, researchers found that 90% of technical team members from the four ECCE sectors believed that positive working approaches had developed, at least to some extent, as the plan was being implemented. The pivotal role that IECD plays in coordinating the plan has evolved, through academic working sessions, supportive committee meetings, and the development of monitoring structures. The evaluation report pointed out two major impacts of the plan: it has promoted multi-level collaborative action and developed effective multi-sectorial coordination. The quality of the relationship is also important. Two important ingredients in the collaborative efforts are interpersonal consideration and a professional approach (Choppy, 2015). Also crucial is the element of facilitation: technical teams feel they are being supported by IECD, and they recognize that the IECD inputs are valuable. All parties partner when the IECD works alongside team members to implement a specific project and to learn from their expertise. These processes—subtle and complex but rewarding—have guided the IECD in its practice and moved ECCE forward.

Policy research

Within the context of the ECCE system the power of research is being harnessed to instigate change. Research findings are beginning to clarify situations, to point to new directions, and to suggest improvement strategies. Research has also been a useful tool to strengthen coalitions among sectors and other partners, and to reinforce monitoring and reporting. This is best illustrated by one of the historical research studies conducted by the IECD, The National Childminding Study. Its emphasis was on improving ECCE provisions for children 0 to 3 years old; at that time, about 75% of children in that age range were being catered for in unregulated home-based establishments. The study developed an experimental research model to establish the status of the child care services being offered. Another aim was to diffuse the study’s findings through policy briefs that would engage relevant sectors and organizations in consultative dialogue. As convincing evidence from the briefs targeted relevant organizations, it became possible to engage diverse sectors in directly contributing to the developing standards for child care services—standards that those actors became involved in implementing and monitoring. Thus, the research model not only provided policy direction but also propelled ECCE-related organizations into action.

Research has also been widely used as a tool for other functions: monitoring and reporting, providing policy advice, and advocating change. For example, an on-going nationwide study that monitors developmental screening will gather useful information on child development outcomes. Research activities are incorporated into most of the projects in the National Action Plan, in order to monitor the project trajectory and develop indicators, and to measure the effects of programs and interventions. A national survey on ECCE has generated much-needed information on professional and public views of ECCE, which can now be used for advocacy and education campaigns.

What has been the impact?

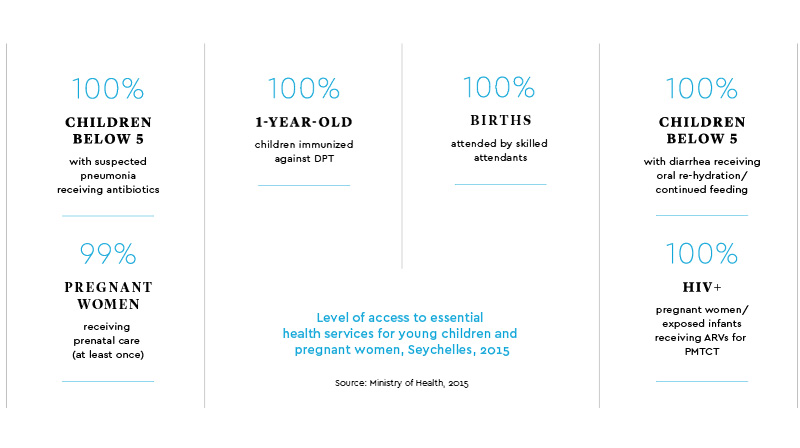

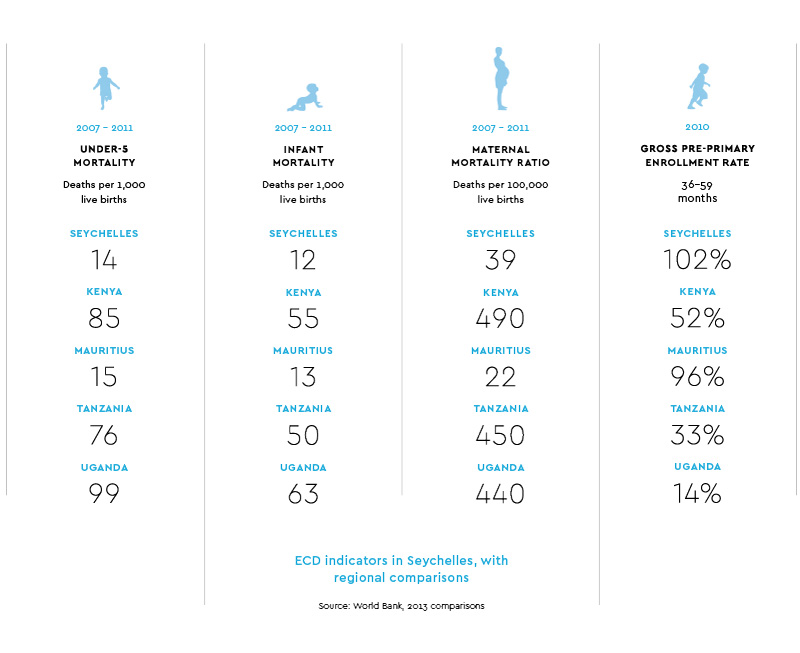

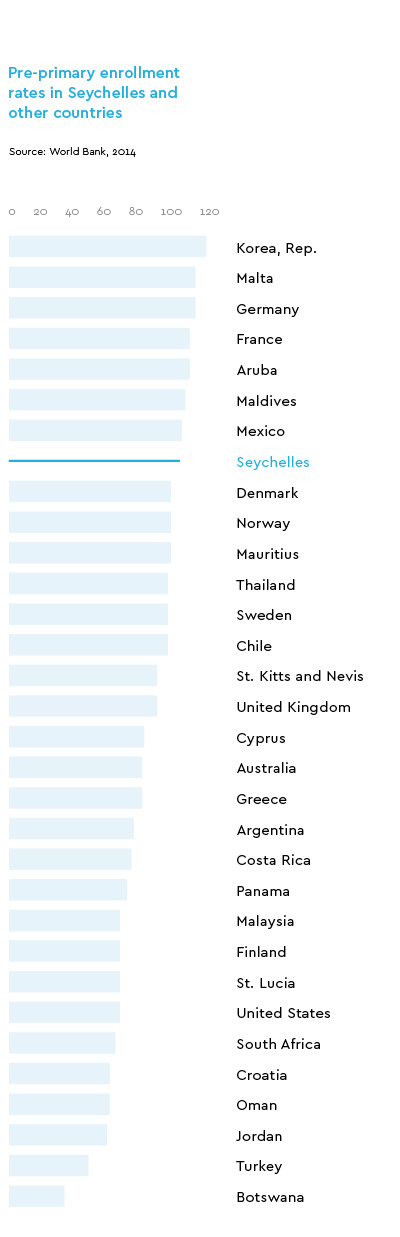

Here we offer three figures that indicate the impact of the ECCE work in Seychelles. The first figure compares some early childhood development (ECD) indicators for Seychelles with those of other nations in the region. The second figure illustrates access to essential health care for mothers and young children in Seychelles. The third figure shows the country’s pre-primary enrollment rates, which are higher than those in several developed nations.

Photograph: Alamy

Reflections

As part of the global challenge to improve ECCE provisions, Seychelles has made rapid progress in reforming and transforming its ECCE system to make it more sustainable and resilient. It has been a journey of determination, perseverance, and grit. At the heart of the change were the nationwide efforts to garner skills, expertise, and knowledge, along with commitment to participate in the change process. High-level political endorsements were the first step in advancing the ECCE agenda. Then the national policy framework established the vision and provided the impetus for change; since a leading agency was established by law, it has worked towards integration and coherence. Selected priorities are being addressed through the National Action Plan, strong collaborative structures have been built, research activities have led to policy dialogue forums, and a strong focus has been placed on monitoring. IECD, collaborating with national partners and supported at the ministerial level, has played a dynamic role in reinforcing, supporting, and refining the ECCE system in Seychelles. To ensure that the system will be sustainable and resilient, IECD has proactively sought additional support from the private sector and from international partners, mainly in the form of funding and technical assistance. It carried out consultative sessions on ECCE projects with a range of organizations to capture interest; it signed memoranda of understanding, mobilized funds, and arranged technical assistance from IBE-UNESCO and the World Bank. Funding, as always, is a fundamental challenge to making reforms, sustaining them, and consolidating change. Funding for ECCE is being supported by local and international partners, through advocacy campaigns, private and public sponsors, donor agencies, and convocations of experts.

References

Choppy, S. (2015). Evaluation report of National Action Plan for ECCE 2013-2014. Seychelles: Institute of Early Childhood Development.

Marope, P.T.M., and Kaga, Y. (Eds.) (2015). Investing against evidence. The global state of early childhood care and education. Education on the Move Series. Paris: UNESCO.

Ministry of Health, Republic of Seychelles (2015). Statistics. http://www.health.gov.sc/index.php/statistics/

World Bank (2013). Seychelles early childhood development. Systems Approach for Better Education Results (SABER) country report. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (2014). Seychelles: Programmatic public expenditure review policy notes – health education and investment management. Washington, DC: World Bank.