Knowledge

Malaysia: Women in STEM

How is Malaysia tilting the gender balance?

March 24, 2018

Malaysia aims at closing the gender gap in STEM education and professions: a transformative process, with positive implications for the country’s development.

Photograph: Alamy

By Honourable Dato’ Seri Mahdzir Khalid

24/03/ 2018

·

- Share

Enhancing human potential is crucial, and the key to improving the wellbeing of individuals and communities. Each citizen must be empowered if they are to have the skills to earn a living and collectively usher the country toward a higher living standard. But history shows that women have not always been provided equal opportunities to gain an education and to master higher-level skills. Traditionally perceived as family caregivers, women have long been sidelined in national and international development efforts. Realizing this, many countries have embarked on productive plans to gradually increase opportunities for women to access education and training in higher skills. The Education 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, spearheaded by UNESCO and supported by its Member States, has a clear vision for enhancing female participation in education. Likewise, the emphasis on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) is considered a driving force for national and global economic development. These developments make it imperative that both women and men play important roles. And yet, women account for only 28% of researchers worldwide and the percentage drops at higher levels of decision-making (UNESCO, 2015a). Embracing for decades the need for both STEM and equal opportunities for women, Malaysia has achieved a great deal and intends to keep raising the proportions of women who participate in STEM and other arenas.

Women’s participation in STEM: The current situation in Malaysia

The Malaysian government identified STEM as one of the catalysts for transforming the country into a developed nation by 2020, ensuring sufficient STEM-related human capital, resources, and infrastructure. The government also recognizes the need to capitalize on female participation to promote its economic and national development (Mohamed, 2011). Since the early 1970s, the country has made great efforts to increase the percentage of women in the workforce; one result is an increase of 95%, across all fields, from 2,374,300 in 1990 to 4,689,700 in 2012 (MoHR, 2012).

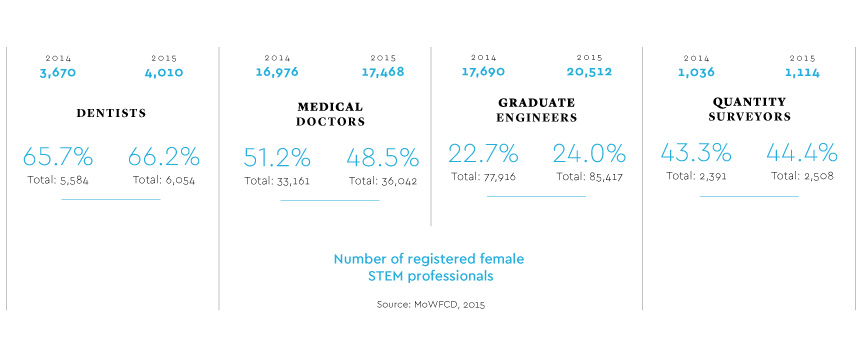

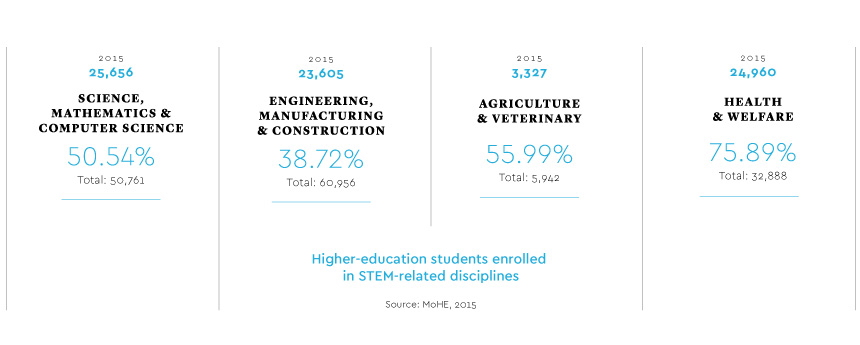

On the education front, in 2015, women constituted more than 50% of students across all STEM-related courses, except engineering, in third-level education. Malaysian girls are performing well in STEM from primary schools up to university, in both academic and extracurricular areas. As of 2015, the enrolment rate was 84.6% for preschool children, 98% for primary school, 92.5% for lower secondary, and 85% for upper secondary. Half of these children are girls (MoE, 2016).

The transformation process

In the 1960s, Malaysia faced the reality of gender disparity in education and in the workplace; girls’ enrolment in schools, especially secondary schools, was low, and few women were in the professions, particularly in the fields of science and technology, which were largely male dominated. Gender stereotyping was common in the society: women were expected to marry young, bear children, and do housework. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the government spearheaded many education plans that aimed to provide education to all children regardless of gender. All children were required to attend and complete primary education as stipulated in the Education Act of 1996, which resulted in the establishment of more schools in urban, suburban, and rural areas. In 2003, compulsory education was extended to lower secondary school, assuring 9 years of education. Education has been provided free for all students since 2012. With this background, Malaysia has achieved nearly universal education at both primary and secondary levels (MoE, 2015).

In the 1970s, the government of Malaysia focused on the need for more STEM students, both girls and boys, in order to become a developed nation, and the 60:40 Policy was formulated. This policy encourages students with good scores on science and mathematics tests at the lower secondary school level to enter the science stream at the upper secondary level, and take more STEM subjects. At present, 46.72% of students in upper secondary 5, the last year of upper secondary school, choose the STEM stream; 48.85% of the girls are in the STEM stream (MoE, 2014). This policy has led to a significant number of Malaysians becoming qualified in STEM fields.

Alongside this effort to provide education for all and to emphasize STEM education for all, the Malaysian government expanded girls’ schools, providing the impetus girls needed to participate more fully in education. First established in 1947, girls’ schools have created a safe, equal learning environment where female students are encouraged to express themselves actively and take on leadership roles as they participate in learning such as STEM activities and experiments (CDD, 2015). Currently there are 84 girls’ schools and 6 girls’ residential science schools.

In addition to the girls’ schools, the government established residential science schools to provide quality STEM education. The first residential school, Malay College Kuala Kangsar (MCKK), was established in 1905. Currently, we have 69 fully residential science schools across the country; 6 for boys, 6 for girls, and 57 co-ed. Apart from this, the first residential MARA Junior Science College (MJSC) was built in 1972 by the People’s Trust Council; now there are 51 MJSCs across the country. Over the years, other residential science schools and MJSCs have succeeded in producing many outstanding STEM professionals.

Key factors promoting women’s participation in STEM

Two key factors encourage Malaysian girls to participate in STEM: the policies themselves, and the attention the government places on implementing them. Ultimately aiming to benefit both girls and boys, the policies set STEM up as the basis for nation building, mainstreaming STEM in education. What emphasizes the centrality of women’s participation is the implementation of gender-specific policies and development plans that particularly target women and girls.

Several policies are crucial in this effort. The New Economic Model (NEM), launched in 2010, aims to transform Malaysia into an inclusive and sustainable developed nation by 2020. NEM focuses on stimulating economic growth by improving worker productivity across all sectors of society. Meanwhile, the National Policy on Science, Technology & Innovation (NPSTI) 2013–2020 focuses on strategies to make Malaysia a sustainable and inclusive knowledge-oriented economy. Both NEM and NPSTI highlight the pivotal role of STEM education in empowering both women and men to achieve its vision of a scientifically advanced nation experiencing socio-economic transformation and inclusive growth. In addition, strengthening STEM is a key element in the Malaysia Education Blueprint (MEB) 2013–2025, a comprehensive plan produced after a comprehensive review of the education system. Likewise, the Malaysia Education Blueprint – Higher Education (MEB-HE) 2015–2025 identifies technical and vocational education and training (TVET) as a STEM initiative to be focused on over the next decade.

In addition, Malaysia has a national women’s policy, the Malaysia Woman Policy (MWP), established nearly 30 years ago and revised in 2009. It aims to develop women’s human capital and to empower women to be competent, resilient, knowledgeable, visionary, creative, and innovative while demonstrating moral values. In fact, the MWP resulted from Malaysia’s strong support for the universal principles of gender equality and non-discrimination in the regional and international cooperative Action Plan for the Development of Women. As the policy was developed further, it outlined actions to be taken by government agencies, NGOs, the private sector, and civil society. The policy seeks to empower women in areas such as e-commerce, so they can gain the knowledge and skills they need to function as entrepreneurs. This endeavor will eventually eliminate the discrimination and marginalization that affect women in the nation’s development efforts.

Key lessons

Malaysia has succeeded in engaging more girls in STEM mostly by formulating appropriate and comprehensive policies and ensuring they are implemented efficiently through thorough action plans and regular monitoring, along with quality education and sound professional development among teachers.

Establishing girls’ schools to capitalize on their potential through education

Given the influences of Malaysian society and culture, Malaysian women have traditionally been raised to be less assertive in a male-dominated community. The gender stereotyping of boys as better in ‘smarter’ subjects such as science and mathematics has kept girls from progressing in STEM fields. Thus, girls needed a less inhibiting environment, one where they could express themselves freely and where they would have to play an active role in STEM learning. Hence the policy of girls’ schools was formulated to capitalize on girls’ potential through such a secure, inclusive, and equal learning environment. In such schools, girls are encouraged to express themselves freely and to be more independent and assertive (CDD, 2015a). That these schools are succeeding is clear, as their students have received many innovation awards and participated in many STEM projects (CDD, 2015a).

Empowering female role models to inspire girls as students

Female role models are a clear motivator, as they encourage more girls to enter STEM. Many women are involved in STEM fields in Malaysia, specifically in the health sciences and medicine; in a growing trend, more are venturing into the physical sciences and engineering. These women professionals can be a powerful instrument in encouraging girls to participate in STEM. A study conducted by the Ministry of Education (CDD 2015b) looked at the reasons girls chose a STEM course or career, and found five key factors: their interest in exploring and doing experiments, career guidance, inspiring teachers, role models, and peer influence. Clearly, relationships play a key role in their choice; this finding highlights the need to adequately train teachers and school counselors to engage more girls in STEM fields—and to continue connecting them to role models.

Using gender-inclusive pedagogy

Teachers are key players in including girls in inquiry-based activities and collaborative innovative STEM projects. Female role models who participated in the CDD (2015b) study mentioned above cited the experiments they conducted in school as a factor that motivated them to pursue STEM. Pedagogies that promote exploration and inquiry-based learning are core to the Malaysian STEM curriculum. Teacher training in Malaysia focuses on this acquisition of STEM practices where students explore and investigate real-life issues. Gender equality is accomplished as female and male students have greater and equal access and opportunities to explore and be involved in STEM projects.

Involving the community

Getting more girls involved is not the sole responsibility of schools; it also relies on the whole community. Government sectors need to work together with NGOs, professional bodies, and other civil organizations to get rid of gender stereotyping. Malaysia has enacted many STEM-related laws. The most prominent are the Academy of Sciences Malaysia Act of 1994, the Chemists Act of 1975, and the Engineers Act of 1967, revised in 2007. Each act is implemented through an institution or professional body, such as the Academy of Sciences or Institute of Chemistry Malaysia, or the relevant ministry. These professional bodies bring together specialized STEM experts to provide advice to the government and the practicing scientists. Their activities focus on motivating students to pursue STEM-related courses and become STEM professionals regardless of gender, at the school and university level.

The IBE-UNESCO Girls in STEM initiative

Malaysia has always been committed to working together with UNESCO in its programs and activities to promote and enhance the quality of education among its Member States. Malaysia’s longstanding commitment began in 1958 when it first joined UNESCO. It has been a member of the executive board for several terms, including the current 2015–2019 term. In April 2015, the Malaysian government approved a proposal by IBE-UNESCO to work collaboratively on an initiative to strengthen STEM curricula for girls. The initiative aims to increase female knowledge and engagement in STEM through the creation of gender-responsive STEM education for Member States in Asia and the Pacific (Cambodia and Vietnam) and Africa (Kenya and Nigeria).

Experts from Malaysia’s Ministry of Education worked together with those in SEAMEO RECSAM, IBE-UNESCO, and the beneficiary countries at a series of workshops and dialogues to create a roadmap to bring more girls into STEM. The roadmap contains plans to formulate STEM education policies, and to develop gender-responsive STEM curricula, teacher education programs, and resources. This effort has already borne several fruits: the inaugural Cambodian STEM education policy, the on-going development of the STEM curriculum framework, and for Kenya, a plan for education reform and a STEM curriculum. The Malaysian experts, working with IBE-UNESCO staff, have also prepared a training tool: a resource pack for gender-responsive STEM education. The resource pack was developed to enhance the skills and readiness of participants in each country, giving them the confidence to share with colleagues at home their knowledge and experiences about strengthening STEM education. This resource pack will be used as technical guidance for the beneficiary countries and the Member States.

Challenges and future frontiers

One interesting challenge has been identified: boys are in danger of being sidelined, as the emphasis is placed on engaging girls in STEM. Thus, we must aim to maintain the balance, encouraging both boys and girls in all programs and activities, to avoid the ‘lost boys’ syndrome. Effective strategies need to be developed to foster and maintain gender equality. It would be ideal to examine the current policies, curricula, and practices to ensure that they are designed in gender-responsive ways, and also to encourage both girls and boys to work together on school projects, and to consider each other as equal partners.

Cultivating a culture that values STEM at an early age is also a challenge to be reckoned with. Children should be encouraged to engage in hands-on activities, and should be provided with opportunities to fulfill their natural curiosity, practice basic science skills, and investigate their environment instead of being forced to regurgitate science facts. It is also worthwhile to identify and prevent possible hidden gender biases within the society that can hinder both girls and boys from participating, and progressing, in STEM.

Envisioning a bright future where gender equality is guaranteed across all strata of society, Malaysia continues to strive to create an inclusive, respectful, and supportive culture: a culture where both women and men work together as pillars of support for each other. Malaysia has achieved considerable gender equality and inclusiveness in STEM fields so far. Yet, it will make even more effort to improve the quality of STEM education and guarantee a sufficient supply of STEM resources and human resources to lead the country to an advanced level, to benefit both Malaysia and the world at large. Meanwhile, Malaysia will continue to play its role as an advocate through sharing its know-how and experiences to help realize gender-responsive STEM education worldwide.

References

CDD [Curriculum Development Division, Bahagian Pembangunan Kurikulum] (2015a). Kajian pelibatan murid perempuan dalam STEM di sekolah berasrama penuh dan sekolah harian [A study on involvement of girl students in STEM in residential schools and in day schools]. Putrajaya: Ministry of Education.

CDD (2015b). Kajian faktor persekolahan yang mempengaruhi wanita yang berjaya dalam STEM [A study on schooling factors for women role models in STEM]. Putrajaya: Ministry of Education.

MoE [Ministry of Education] (2014). Bahagian perancangan pendidikan dan penyelidikan: Bilangan murid dalam STEM [Educational planning and research in education: Enrolment of students in STEM]. Unpublished report. Putrajaya: MoE.

MoE (2015). Malaysia Education for All: End of decade review report, 2000-2015. Putrajaya: MoE.

MoE (2016). Malaysia education blueprint 2013-2025, Annual report 2015. Putrajaya: MoE.

MoHE [Ministry of Higher Education] (2015). Makro-Institusi pendidikan tinggi [Macro-higher education institutions]. In Statistik Pendidikan Tinggi [Higher education statistics]. Putrajaya: MoHE.

MoHR [Ministry of Human Resources] (2012). Labour and human resources statistics 2012. Putrajaya: MoHR.

MoWFCD [Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development] (2015). Statistics on women, family and community Malaysia 2015. Putrajaya: MoWFCD.

Mohamed, N. J. (2011). Statement by the Honorable Mr. Nur Jazlan Mohamed, Member of Parliament and Representative of Malaysia at the Third Committee of the 66th Session of the United Nations General Assembly. New York, 11 October 2011.

UNESCO (2015a). A complex formula: Girls in STEM in Asia. Paris: UNESCO.